Florida’s History of Crime and Drug Culture

Florida is the Spanish word for “flowery land,” and the term describes the Sunshine State well. It is the third most populous state in the United States. Florida straddles the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Straits of Florida, giving it the longest coastline in the contiguous United States (1,350 miles). That strategic location has given it a long history of tourism, agriculture, and trade. Unfortunately, not all of that trade has been savory, and drug lords and cartel bosses from South America have long looked at Florida’s long coasts as their key to the North American drug market.

Florida is the Spanish word for “flowery land,” and the term describes the Sunshine State well. It is the third most populous state in the United States. Florida straddles the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Straits of Florida, giving it the longest coastline in the contiguous United States (1,350 miles). That strategic location has given it a long history of tourism, agriculture, and trade. Unfortunately, not all of that trade has been savory, and drug lords and cartel bosses from South America have long looked at Florida’s long coasts as their key to the North American drug market.

History of Drug Crimes in Florida

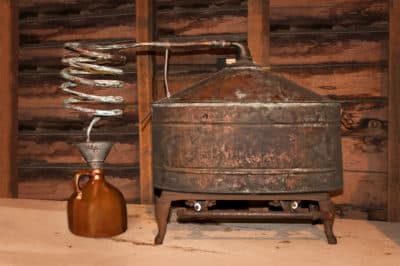

Florida’s history with the trade of contraband goes back a long way. During the Prohibition era, the state was home to a number of nightspots that celebrated the vice of alcohol production, transportation, and sale in the face of a seethingly unpopular and poorly enforced Eighteenth Amendment. The Orlando Sentinel writes of how the Flamingo Cafe became a hotbed of fashion, style, and buying and selling drinks. High-society customers happily knocked back concoctions imported from the Caribbean islands, unmolested by the police and the sheriff. “Prohibition,” writes a former associate editor of the Sentinel, “was as unpopular as the plague,” so much so that even the mayor of Orlando would be seen at the establishment.1

Florida’s history with the trade of contraband goes back a long way. During the Prohibition era, the state was home to a number of nightspots that celebrated the vice of alcohol production, transportation, and sale in the face of a seethingly unpopular and poorly enforced Eighteenth Amendment. The Orlando Sentinel writes of how the Flamingo Cafe became a hotbed of fashion, style, and buying and selling drinks. High-society customers happily knocked back concoctions imported from the Caribbean islands, unmolested by the police and the sheriff. “Prohibition,” writes a former associate editor of the Sentinel, “was as unpopular as the plague,” so much so that even the mayor of Orlando would be seen at the establishment.1

The Miami New Times explains that during the days of Prohibition, the city was the “Wild West” of the times, with both the nostalgic and grimmer elements of the Roaring Twenties being played out.[2] Miami-Dade County, today the most populous county in the state, was a center of rum-running when Prohibition was at its peak. This entailed bootleggers proudly showing off their cash hauls, and the Miami River being the scene of violent gun battles between police, gangs, and rival gangs. All the while, “liquor flowed in on the tides.”

A historian notes that South Florida snubbed Prohibition to a greater degree than any other part of the country, an ironic badge of honor that hints at the region’s future battles with the trade of illegal substances.

Lawlessness in FL

When the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect on January 16, 1920, the immediate impact was over a decade of gambling, prostitution, bootlegging, violence, corruption, and disregard for the law. In 2008, the Miami Heraldcompared the situation to what was in Florida’s future – the organized crime of the 1950s, the “cocaine Cowboys” of the 1980s, the nightclub drug scene of the modern era – and called the days of Prohibition “the most protracted and pervasive period of lawlessness and debauchery” in the region’s history.

When the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect on January 16, 1920, the immediate impact was over a decade of gambling, prostitution, bootlegging, violence, corruption, and disregard for the law. In 2008, the Miami Heraldcompared the situation to what was in Florida’s future – the organized crime of the 1950s, the “cocaine Cowboys” of the 1980s, the nightclub drug scene of the modern era – and called the days of Prohibition “the most protracted and pervasive period of lawlessness and debauchery” in the region’s history.

As has been widely argued and accepted in the generations that followed, Prohibition’s intention to clamp down on crime and social ills had the opposite effect; the move to enforce temperance instead created an empire from rum-running and lined the pockets of people who were willing to make a buck to subvert the law. While this was felt all across the United States, it was most keenly felt in South Florida, with its thousands of miles of coastline and remoteness from national law enforcement. The combination made the area “the perfect hub” for illegal activity.

Such was the extent to which Prohibition flopped in Florida that a historian wrote that Miami’s implementation of the so-called “noble experiment” was considered a joke, and the region’s bootlegging was as much of a tourist attraction as the palm trees and beaches that have become iconic representations of the state. Only 2.5 years after the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect, a Chicago newspaper said the Floridian coast was a “paradise” for bootleggers.

Fighting Prohibition Laws

Prohibition may have been unpopular, but it was the law. While local officials were more than happy to turn a blind eye to the happenings, federal law enforcement took a much dimmer view. Thus began a deadly game of cat-and-mouse between the US Coast Guard and rum-runners trying to import alcohol from the Caribbean islands. Smugglers used World War I airplane engines in their speedboats to dart back and forth between the Bahamas and various points on the coast of Miami-Dade and Broward counties, and slipped into Miami’s dense network of canals to evade capture.

However, the tactics were not always successful. As a sign of the times, the court of public opinion was not always on the side of law enforcement. In February 1926, when E.W “Red” Shannon, known as “King of the Florida Smugglers,” was shot dead by Coast Guardsmen

while approaching Miami Beach in his boot loaded with 170 cases of liquor, witnesses to the incident threatened to file an official protest, claiming the Coast Guard’s measures were unjustified.

Four months later, the crew of another Coast Guard patrol board was greeted with “catcalls, boos and loud hisses” from spectators as it sailed down Miami River after a failed attempt to hunt down rum-runners.

Two months after the shooting on the Miami River, seven federal Prohibition agents were shot at by three men, presumed to be moonshiners. The agents had been conducting raids on moonshine distilleries in the Everglades.

Three years after that in 1929, a Coast Guard crew fired 200 shots at a rum-runner on the Miami River, an incident that made national headlines and caused outrage; the mayor of Miami called the Coast Guard’s actions “worse than a disease.”

Such was the disdain for the federal government’s enforcement of the Eighteenth Amendment, that the Associated Press reported that federal prisoners being held in the Dade County jail were released every night to further their bootlegging businesses (with a cut of the proceeds going into the pocket of the officials who unofficially approved of the releases). In 1927, Prohibition agents conducted mass arrests of deputies and police officers of Broward County, in an attempt to crack down on what the Associated Press called “one of the biggest liquor conspiracies in the country.”

Notorious Mobsters of Florida

But the federal government’s attempts to impose some form of order in Florida only scratched the surface of what was happening in the state. So much alcohol flowed through Fort Lauderdale that the city was given the nickname of “Fort Liquordale.”

Perhaps nothing more encapsulates how much Florida had become a center for bootlegging and rum-running than the 1928 arrival of “the king of bootlegging”: Al Capone, whom The New York Times called “a violent, intimidating and unpredictable force,” whose legacy continues to haunt the city of Chicago, where Capone reigned as boss for seven years.3 But it was in Florida – specifically, a $40,000 estate in Palm Springs – where Capone found respite from the repercussions of his bloodshed in Chicago. Even as the city council passed a unanimous resolution to ban Capone from taking residence in the area, the mayor of Palm Springs not only allowed Capone to remain, his real estate firm sold Capone – who the Sun Sentinel called “the most notorious mobster of them all” – the very house he lived in.4

Perhaps nothing more encapsulates how much Florida had become a center for bootlegging and rum-running than the 1928 arrival of “the king of bootlegging”: Al Capone, whom The New York Times called “a violent, intimidating and unpredictable force,” whose legacy continues to haunt the city of Chicago, where Capone reigned as boss for seven years.3 But it was in Florida – specifically, a $40,000 estate in Palm Springs – where Capone found respite from the repercussions of his bloodshed in Chicago. Even as the city council passed a unanimous resolution to ban Capone from taking residence in the area, the mayor of Palm Springs not only allowed Capone to remain, his real estate firm sold Capone – who the Sun Sentinel called “the most notorious mobster of them all” – the very house he lived in.4

It was an indication of how far the pendulum had swung in favor of the bootleggers and rum-runners (and the mobsters who pulled all the strings). In April 1932, five Prohibition agents attempted to raid a restaurant on Miami Beach. The men were met with such a mob of resistance that they barricaded themselves inside the restaurant and called for help. Outside the restaurant, patrons slashed the agents’ car’s tires.

In December 1933, US Congress passed the only Amendment in the US Constitution that repealed a prior Amendment. After almost 14 years of Prohibition, the Twenty-first Amendment struck it down and legalized (with regulatory oversight) the production, transportation, and sale of alcohol.

The Cuban Connection

Al Capone died in his Palm Springs home in 1947, but his move to Florida, and his influence on the thriving bootlegging market in the area, changed how the criminal world saw Florida. One of them was Meyer Lansky, who was one of the architects of a confederation of criminal organizations that stretched across the United States. While Capone was a bloodthirsty mob boss, Lansky was an accountant; his area of specialty was gambling, which he developed in casinos he owned across the world, including in Florida, Los Angeles, the Bahamas, and Cuba.

Lansky first arrived in South Florida during the gambling boom of the 1930s. His targets were known as carpet joints, a term for honest casinos that would never cheat a customer out of his winnings, but would nonetheless pay off corrupt sheriffs and other officials to be allowed to operate as Lansky saw fit.

Lansky’s businesses were wildly successful (so much so that rival crime bosses agreed to conduct their businesses peacefully, so as not to incur undue attention from law enforcement), but while Capone operated in spite of the federal government, Lansky had to contend with an FBI that was much more resolved to end organized crime than its predecessors. As Lansky’s fortunes grew, so did the government’s scrutiny, to the point where running gambling operations in such flashy and notable locations as casinos became too risky. Instead, Lansky and his partners turned to horseracing and sports betting, while also traveling across the Gulf of Mexico to Cuba, where they were warmly welcomed by Fulgencio Batista, who effectively allowed Lansky to control the entire gambling industry in Cuba (in exchange for kickbacks).

The Mayor of Miami Beach

However, the whole world was changing, and the American Mafia found itself being left behind. Lansky enjoyed unimaginable success in Cuba for seven years, but the leaders of the Cuban Revolution had no time for American gangsters and their endless greed (especially gangsters who had been welcomed by the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista). Between 1959 and 1960, Lansky’s Cuban casinos were either closed down or razed to the ground as part of the Cuban Revolution, and Lansky was forced to flee the islands after losing over $7 million.

With the federal government of the United States waiting to arrest him, Lansky tried to seek asylum in his ethnic homeland of Israel, but in light of Lansky’s criminal ties, the Israeli government deported him back to the United States in 1972. The government tried to pin Lansky on charges of tax evasion and conspiracy, but their case was weak and he was easily acquitted in 1974.

Lansky joined a number of other high-profile criminals who made Florida their home, even enjoying a degree of popularity like his former mob boss, Al Capone. Notwithstanding the local media referring to Lansky as “Public Enemy No. 1” (a title also bestowed upon Capone in his day), Lansky’s daughter recalls receiving letters written to the “Mayor of Miami Beach.”

Meyer Lansky never left Miami Beach. He died of lung cancer in 1983 at 80 years old. Forbes magazine and the FBI estimated that Lansky was worth $300 million, which would have made him the most financially successful mobster in history.5 The Sun Sentinel remembers Lansky as “one of the most significant mob figures of the 20th century.”6

Why Not the Mafia?

Lansky cooling his heels in Florida is emblematic of a trend that many gangsters from the cold mob strongholds of the Northeast and Midwest find attractive; not only is the state open for business, but the tropical weather allows them to relax while they conduct their business. An agent for the US Drug Enforcement Administration estimates that “hundreds” of mobsters from Chicago, New York, and New Orleans would make South Florida their second (or even their retirement) home.

Lansky cooling his heels in Florida is emblematic of a trend that many gangsters from the cold mob strongholds of the Northeast and Midwest find attractive; not only is the state open for business, but the tropical weather allows them to relax while they conduct their business. An agent for the US Drug Enforcement Administration estimates that “hundreds” of mobsters from Chicago, New York, and New Orleans would make South Florida their second (or even their retirement) home.

In the heydey of the Italian American Mafia (led by the five organized criminal organizations of New York), it was decided that Florida would remain “open,” meaning that no one crime family could operate unilaterally. Such was the situation that in 1968, a state crime commission reported that Dade and Broward Counties had become a destination for a number of known Mafia leaders and their associates.

While figures like Al Capone and Meyer Lansky are best known from history books and dramatic depictions on film and television, more recent figures like John Gotti (the late boss of the Gambino crime family) and Nicodemo Scarfo (the boss of the Philadelphia crime family, currently serving a life sentence) both had residences in Fort Lauderdale.

A professor at Nova Southeastern University Law School explains that the Mafia’s continued interest in Florida is because the Sunshine State still holds all the attraction that it did in the 1930s: accessible coastlines, a long history of defying law enforcement, and warm weather. Everybody wants to be in South Florida, says the professor, so why not the Mafia?7

The Roaring 2000s

But whether due to stronger law enforcement, the passing of a generation, or a changing criminal landscape, the power and influence of the Italian American Mafia have declined. The void has been filled by criminal figures from Russia, Israel, and most notably South America, who have expanded the illegal businesses market of Florida beyond gambling, into money laundering and the drug trade.

The New York Times reports that in Miami’s “imported mob scene,” a new generation of criminals and drug smugglers are using the Internet and Florida’s key location to conduct their business. One recent case involved two young Hasidic Jews working with an Israeli man to bring thousands of ecstasy pills, manufactured in Amsterdam, to smugglers in Miami Beach. In a strange kind of homage to organized crime’s northeastern roots, Israeli gangsters have gotten strippers from bars in New York to transport ecstasy from across the Atlantic Ocean, up and down the East Coast.8

Part of the lure comes from Miami’s attractive (in more ways than one) nightlife, hearkening back to the days of speakeasies and bootleggers. In 2000, The New York Times reported on how nightclubs in South Beach have inspired “precarious excesses,” such as opening their doors to patrons at 4 a.m. The chief of the Miami Beach Police estimated that up to 80 percent of the people who frequent such establishments use recreational drugs.

The chief asked the city of Miami Beach to shutter the after-hours clubs, but city commissioners felt that the clubs provided an economic boost, and furthered the image of Miami Beach as a hotspot of culture and entertainment. In the words of the mayor of South Beach, the place is “roaring.”9

The King of Cocaine

But perhaps the biggest threat to the public health of Florida comes not from the Italian American Mafia struggling for relevance, or from Russian and Israeli gangsters trying to seize a lucrative market. With politicians, law enforcement, and anti-immigration activists training their sights on the US-Mexico border, drug cartels in Central and South America have found Florida’s long, poorly policed coastlines very attractive.

But perhaps the biggest threat to the public health of Florida comes not from the Italian American Mafia struggling for relevance, or from Russian and Israeli gangsters trying to seize a lucrative market. With politicians, law enforcement, and anti-immigration activists training their sights on the US-Mexico border, drug cartels in Central and South America have found Florida’s long, poorly policed coastlines very attractive.

This interest is far from recent. Even as Meyer Lansky was looking forward to a quiet retirement, the 1970s and 1980s were shaping up to be big years for gangs that traced their origins to Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru – traditionally, the three biggest cocaine-producing countries in the world.[10] Pablo Escobar, forever remembered as the “King of Cocaine” who smuggled 80 percent of America’s cocaine across the border, used an island 200 miles southeast of Florida’s coast, to coordinate his shipments and distribution operations in South Florida.11 And, like his Italian-American Mafioso predecessors, Escobar even maintained a residence in Florida, a mansion that was purchased in 2014 for $9.65 million.12

Florida’s Cocaine Cowboys

Pablo Escobar is a household name across the United States and his native Colombia, where he continues to be revered for his Robin Hood-like image. However, his Floridian empire might have been very small if not for a woman known as the “Cocaine Godmother,” Griselda Blanco, who was the primary architect of Miami’s Colombian/South American drug trade. Blanco’s arrival in Florida was the catalyst of the Miami Drug War, with a Miami attorney reflecting that Griselda Blanco’s actions were what forced the US government to acknowledge that Miami had a serious cocaine problem. The response was to create a taskforce comprised of members of the Drug Enforcement Administration and members of the Miami-Dade Police Department.

While the Italian-American Mafia families of New York agreed to conduct their Floridian business peacefully, so as not to draw law enforcement attention, Griselda Blanco had no such compunctions. In Colombia, explains Maxim magazine, cocaine (and the money that comes with it) is stronger than loyalty. It’s why Blanco shot her husband and business partner to death, and why she had no trouble ordering the killings of over 250 people as she solidified her grip on Miami.

Blanco had the means and bloodlust to bring Florida under her thumb, but she also had a good sense of timing. The local cocaine market was already a healthy one, thanks to the influx of Cuban refugees. Other drug lords had their eyes on using Florida as a gateway to the rest of the United States, but Blanco wanted the Sunshine State all to herself.

Her reign of terror gave rise to the “Cocaine Cowboys” of Florida during the 1980s – cartel soldiers who would do the unthinkable, and target women and children as part of Blanco’s war against other dealers.13 It was a brutal strategy, but an effective one. In time, Blanco’s distribution network stretched from one coast of Florida to another, bringing in $80 million every month. Her penthouse on Biscayne Bay hosted exotic cars and cocaine-fueled sex parties.

Eventually, Blanco’s many enemies drove her into hiding. She fled to California, but was arrested by the Drug Enforcement Administration in 1985, held without bail for 10 years, deported back to Colombia in 2004, and assassinated in 2012.14 Maxim magazine referred to her as one of the most ruthless drug lords in history.15

The Rise and Fall of the Cali Cartel

Pablo Escobar filled the void left by Blanco’s death and took the Miami drug trade to new heights. However, after his own violent demise in 1993, brothers Miguel and Gilberto Rodriguez Orejuela, founders of the Cali Cartel, took over. Their use of Escobar’s platform gave the Cali Cartel control over 80 percent of the world’s cocaine trade, making more than $7 billion a year and becoming “the most successful and prolific criminal enterprise in history.”16

The Orejuela brothers managed to avoid the grisly fates that befell Escobar and Griselda Blanco, but big drug busts conducted in their Floridian distribution center were their undoing. In 2006, they were put on trial in Miami, pled guilty to importing cocaine, gave up $21 billion in assets, and were given 30-year prison sentences.17

Escobar, Blanco, the Orejuela brothers, and many more of their ilk, are not players on the Miami drug trade scene any more, but the cocaine industry remains as vibrant as ever. It is estimated that while 90 percent of the cocaine imported into America comes through the US-Mexico border, the other 10 percent is transported over the Florida coast. Between 2012 and 2013, US Customs and Border Protection reported a 483 percent increase in the amount of cocaine arriving in Florida, usually brought over from the Caribbean islands on cruise ships and other legal maritime traffic.18, 19

In 2015, the US Attorney for the Southern District of Florida traveled to Colombia with other high-ranking American officials, to talk with President Juan Mantel Santos about how the respective governments could work together to stop Colombian traffickers from using Florida as a landing ground for their American operations. The result was the arrest and indictment of 17 members of Los Urabenos, currently the biggest drug smuggling neo-paramilitary group in Colombia. The leader of the group is on the run, a $5 million bounty on his head; but the Miami Herald is pessimistic that the joint strike against Los Urabenos will yield a long-term solution to Florida’s long history of crime and drug trade.20

Designer Drugs and New Horizons

The future does not look too promising. Designer drugs cooked up in Chinese laboratories and sold over the Internet are “technically not illegal,” but dangerous enough for 275 people in Broward County to have sought medical treatment for consuming the substance colloquially known as flakka by 2015.21 The drugs are considered of dubious legal status because their chemical composition is constantly altered by manufacturers to dodge US import laws, which allows the distributor to euphemistically claim that the substances are not illegal, but also not meant for human consumption.

When a designer drug is inevitably banned, the manufacturers merely tweak the design of their product and release a new shipment. 22 A Broward County detective tells the Washington Post that the manufacturing network in China has thousands of underground labs at its disposal, making liberal use of corrupt officials and poorly enforced exportation laws to get their products to the United States.23

In the same way that Pablo Escobar and the Orejuela brothers made use of the infrastructure left to them by Griselda Blanco, gangs in Hong Kong have also tapped into the pre-existing market. The South China Morning Post reports of communication between Chinese triads and Mexican cartels, with the aim of using the cartel’s networks through Florida to sell methamphetamine. The government of Mexico acknowledged contact between China (the largest meth-producing country in the world) and the Sinaloa cartel (the most powerful drug smuggling syndicate in the world), with the goal of infiltrating the American drug market, which the South China Morning Post described as “insatiable.”24

Florida’s Endless War

To nip the operation in the bud, law enforcement officials from Broward County visited China, and convinced the local authorities to ban the production of flakka, as well as 115 other chemical compounds that are used in the manufacturing of designer drugs. Exportation laws were also improved, leading a spokeswoman for the Drug Enforcement Administration to tell the Sun-Sentinel that the importation of flakka to the United States would be slowed with the halting of the supply from China, a “major supplier” of the drug.

But in the same way that Florida’s history of crime and drug culture runs from the Roaring Twenties to the Cocaine Cowboys, it continues through underground labs in China or speedboats from the Bahamas, and through heroin trafficking rings, which have tapped into the opioid epidemic that has wracked the rest of the country.25

It is telling that even as law enforcement officials marked the success of their visit to China, there was no delusion that the step forward – important as though it may have been – was a significant achievement in the battle to end drug trafficking through the Sunshine State.26

Citations

- “Prohibition Era’s Double Standards Inspired Notorious Orlando Nightspot.” (November 2011). Orlando Sentinel.Accessed April 20, 2016.

- “Sixty Years Before the Cocaine Cowboys, Miami was the Wild West of Prohibition.” (February 2016). Miami New Times. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- “Capone’s Legacy Endures, to Chicago’s Dismay.” (April 2010). The New York Times. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- “The Gangster Next Door.” (September 1989). Sun-Sentinel. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- “Spoiled by Mobsters, Meyer Lansky’s Daughter Recalls Family Men, Not Killers.” (June 2014). Tampa Bay Times. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- “Family of Late U.S. Gangster Wants Compensation for Cuba Hotel.” (December 2015). Sun-Sentinel. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- “Mafia Has a Long History in South Florida and Still Active.” (March 2010). Sun-Sentinel. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “In Miami, an Imported Mob Scene.” (July 2000). The New York Times. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Miami Beach Clubgoers Creating New, Unwanted Image.” (February 2000). The New York Times. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “A Look at Major Drug-Producing Countries.” (February 2008). USA Today. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Pablo Escobar Biography.” (n.d.). Biography.com. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Locked Safe Found in Debris of Pablo Escobar’s Former Mansion in Florida.” (January 2016). The Guardian. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Cocaine Godmother” Griselda Blanco Gunned Down in Colombia.” (September 2012). Miami Herald. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “The Life and Death of “Cocaine Godmother” Griselda Blanco.” (September 2012). Miami Herald. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Searching for the Godmother of Crime.” (June 2010). Maxim. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “A Daring Betrayal Helped Wipe Out Cali Cocaine Cartel.” (February 2007). Seattle Times. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “U.S. Declares Victory Over Cali Cartel.” (June 2014). CNN. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Cocaine Seized in Florida from Trafficking Hub Ecuador.” (March 2015). Business Insider. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Shifting Drug Smuggling Routes Bring Contraband to Florida.” (April 2014). Sun-Sentinel. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Criminal Gangs Are New Threat From Colombian Drug Trafficking Enterprises.” (July 2015). Miami Herald.Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Cheap, Synthetic ‘Flakka’ Dethroning Cocaine on Florida Drug Scene.” (June 2015). Reuters. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Police in Florida Grapple With a Cheap and Dangerous New Drug.” (May 2015). The New York Times. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Deadly Chinese Drugs Are Flooding the U.S., and Police Can’t Stop Them.” (June 2015). Washington Post. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Hong Kong Triads Supply Meth Ingredients to Mexican Drug Cartels.” (January 2014). South China Morning Post. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “Florida Heals from Pill Mill Epidemic.” (August 2014). The Tampa Tribune. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- “China Bans Flakka, South Florida Law Enforcement Officials Visit Beijing.” (November 2015). Sun-Sentinel. Accessed April 21, 2016.

American Addiction Centers (AAC) is committed to delivering original, truthful, accurate, unbiased, and medically current information. We strive to create content that is clear, concise, and easy to understand.

While we are unable to respond to your feedback directly, we'll use this information to improve our online help.